Week 2 Introduction to research

Hello, everyone, and welcome to the first lecture in SLAT7806 Research Methods. My name is Martin, and I am the course coordinator, as well as lecturer for this course, you will hear me pretty much every week when I’m going to be delivering your lecture podcast. We hope that this semester is going to be very rewarding and fulfilling, as we’re learning about different research methodologies and research design, particularly when it comes to second language studies. In today’s podcast, we have two primary goals.

The first one is to talk about what research is. So we’ll start with some definitions of research as an academic process. We will also talk about research in our daily lives and examine whether we do engage in research activities day to day.

The second goal is to discuss the conceptualization of the research project.

Broadly speaking, the course aim is to introduce you to research in language studies; specifically, we’re aiming to provide you with an understanding of the nature and process of research And we’re really looking at a variety of language studies here. It could be second language acquisition research, applied linguistics, linguistics, or learner corpus research. So hopefully, all of you will be able to find something that aligns with your professional aspirations and your academic interests in this course.

So, we will be looking at the steps that are involved in designing a research project, we’re also aiming to achieve comprehension of different aspects and components of research methodology. So, for instance, how do we find participants? How do we design research tools? How do we select what research technique to apply for a specific research question?

Our third aim is to learn how to review, analyze and synthesize secondary sources. For example, you may be reading a textbook chapter, or journal peer reviewed article, which seems to be on the topic that you’re interested in. So, we will go through some key steps on how to identify the crucial components of those secondary sources, and how to put them together in a coherent literature review. We’re also going to give you some hands-on experience in designing and presenting your research proposal. And then finally, our aim is to identify, locate and use materials relevant to your academic interests. Hopefully, after completing this course you’ll be able to use the skills in your further academic career.

Right, so we’re now ready to discuss the content part of today’s podcast. And we’re moving on to the definition and importance of research. We will start with a simple question, what is research? Basically, you will look at research very broadly; research can be any activity that is undertaken to increase our knowledge. So, for instance, before you’re making a significant purchase. If you wanted to buy a car, for example, you would do some research to make sure that the car that you would want to buy is the best option out there for the price that you’re prepared to pay.

-But in terms of academic or scientific research, we define those activities a little bit differently. In particular, we look at research as a systematic approach to finding answers to questions. Now, how are these two definitions different? If you need to pause the recording to think about it, I encourage you to do that. So, go ahead and pause now and try to find the differences. All right, so we’re coming back and what I was trying to get at is that the academic/scientific definition of research assumes a certain structured and ordered process. So, it’s a systematic approach, we have a series of steps that we maybe need to go through.

In addition, the second definition also presupposes formulation of a specific question or a set of questions. So, for instance, if you’re buying a car, sometimes you’re just sort of browsing around and you’re looking at all available models rather than asking which car is the greenest option. But when we’re conducting academic research, before we begin any project, we’re usually required to start with a very particular specific, an answerable research question to ensure that our study does not deviate from this narrow focus.

The research process is traditionally conceived as a series of steps and you start by formulating question that you want to answer, and you also need to keep in mind that that question needs to be specific enough to be able to answer it. So for instance, if you would like to know why learning the second language may be more difficult for adults, but apparently easier for young infants, it would be quite challenging to get a response to that question in a single study. So that means that the question that you have proposed is too general or too broad; to be able to start addressing it, you need to narrow it down first.

Thus, you could say why learning grammatical aspects of particular second language is challenging for adults and they keep making errors when they produce spontaneous speech. So that’s narrowing it down below but we obviously can continue persisting with that. We can say well, okay grammar of English as a second language for, for instance, Spanish learners. Right, and we’ve narrowed this down further. And we can keep going. Then once our question is specific enough, we need to investigate what information is already available on that question. Or maybe sometimes when that particular question has not been addressed, we’ll look at the broad topic that the question fits into.

So, if we’re interested in second language acquisition, we will obviously read some previous literature that has been written in that area to make sure that this question has not been answered and help us continue to narrow down that question, right. So maybe the grammatical aspects have been investigated, but the pronunciation difficulties have not yet been addressed, and therefore, that’s where we would direct our attention.

After we have reviewed the available literature, we decide what new information or, in research terminology, data we need. So, to be able to answer the question, so we need to think what kind of answers we’re looking for? Are we looking for interview data, for instance, where we record speakers produce spontaneous language, and then we may transcribe and look for errors in their spontaneous speech?

After we have decided on what data is needed to answer your question, we work out how are we going to go about collecting this information. And this includes finding the participants and working out which research methodologies we would like to employ and going through who’s actually conducting the type of research that we have intended to conduct.

Step five is evaluating if the collected information does indeed provide an answer to our question. So, for instance, we want to do investigate pronunciation, but for some reason, we have access to written corpus written database of a particular language. So even though this information is good for something else, it doesn’t address our particular area of interest. In this case we need to start collecting new information.

And then, after we have made sure/ascertained that the data we have collected indeed matches our question, we analyze the information and present the results in a way in which our readers or maybe our audience, if we’re presenting at a conference, can understand and interpret our findings. So pretty much we share the results of our research. There are several types of scientific research and all those different types broadly subscribe to the same steps of the research process.

Now, there are two very broad types I’d like to talk to you about today, they are basic or fundamental research and applied research. Basic research is not called that because it’s super easy; It’s just called basic because it’s designed to advance our knowledge in general, regardless of how we may want to apply this knowledge further. So, it’s kind of just trying to get answers for the sake of getting answers, right? For the sake of advancing our knowledge and broadening our understanding about the world around us.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have applied research. And this is a particular group of studies that are designed to address and to solve real life problems. So, it’s not just abstract, general knowledge, we’re actually gaining answers to some of the issues that we encounter in our daily lives. And a more specific part of applied research is what we call action research. And so action research is designed to solve real problems that affect a researcher specifically, so for instance, it could be a teacher doing research about their own teachings, how to improve or to increase students engagement and things like that. For an interpreter and translator, it could be research about their own interpreting or translating practices, how to improve that how to increase the quality of the end product.

Okay, so far we have been talking about research as an exclusively academic endeavor, but it isn’t really the case. In this part of the podcast, I’m going to talk to you about research in our daily lives and we have kind of touched on that a little bit with my example of purchasing a car. But what I would really like to highlight in this part is that we engage in research activities pretty frequently in our daily lives. So, everyday research or our desire to do everyday research is really tied to our innate sense of curiosity. We’re always searching for answers about the world around us. And by searching for those answers, we perform small acts of everyday research. And in a lot of cases, everyday research is a response to everyday problems.

So, let’s consider the following example. Let’s say we are observing a baby crying, let’s say my baby’s crying, even though I don’t have a baby. I think everyone could imagine the situation, it’s quite stressful. And we can definitely say that it could easily fall under the umbrella of “problems” right. So, we would like to solve that problem. So, the research question here is why my baby is crying, which is quite specific. So, we don’t need to even worry about trying to narrow it down any further.

We can form some hypothesis, which is an academic way to call productions certain ideas about different reasons for the baby crying. So we may consider that the baby is hungry or sick, maybe they need a diaper change. So those are our working hypotheses. And after we have formulated these, we start collecting data. So we start observing the situation we start crossing those hypothesis out of our list. So okay, hypothesis one is that baby hungry. So what we’re going to do is to check the last time the baby had food how long it has been since. Then could see if the baby has temperature and then whether the diaper wet or dirty? So after we have examined all those three possibilities, we can say well the baby had some food pretty recently, so food OK check, diapers OK check, but temperature appears to be too high. So, in this instance, we have gained the response to our question, since the temperature is too high, it is likely that the baby is sick. And then after conducting this series of everyday research steps, we are arriving at our response to this problem. So, we need to take action based on our finding. And in that case, it would be taking the baby to the doctor and maybe giving the baby some medicine. And so this is an excellent example of everyday research.

After listening to this component of today’s podcast, I encourage you to think about your own examples where you had to engage in problem solving, in this type of everyday research activities. Let me conclude this part by contrasting everyday and scientific or academic research. So we’re going to go through the table on slide 8 and have a look at the differences between the two research types.

So in terms of the context of knowledge development, in everyday knowledge and practices, we develop our knowledge

based on the pressure to act right once again. So a problem is in front of us and we feel the pressure to resolve that problem. Sometimes it’s the time pressure, so the baby’s crying, we need to act immediately. Sometimes it’s just the pressure. Maybe it could be work pressure, deadlines, things like that. Solving of problems is the priority. Because once the problem is solved, we don’t have to worry about it anymore. And then the routines that we use to solve the problems are usually not put to the question or broken down. So we sort of go through those routines as per tradition, we work on what we think is efficient, and what effectively solves the problems and we continue to implement those routines consistently.

When we talk about scientific or academic research, we are relieved from pressure to act because in many cases, we are asking broader, more general questions that are the ones that we encounter in our everyday lives. And because we’re relieved from the pressure to act, it means that we have more time to systematically analyze the problems and we quoted as our first priority. The routines are put to question broken down, which means that we’re constantly searching for new ways to address similar research questions.

Now we’re moving on to the second row of the table, and we’re going to discuss our ways of knowledge. So in terms of our everyday practices, a lot of the times we act based on intuition, and through this intuition and through experiences, we implicitly or subconsciously, develop certain theories of how we should act in any given situation. And then we go through pragmatic testing of theories; in scientific research, we use scientific theories, what previous researchers have come up with to address specific questions. This means that when we think about a particular question we’re not just acting based on our intuition, we put things to the test. And based on the outcomes of those tests, we consciously try to formulate what it means for the research project.

When conducting scientific research, we use established research methodology. So experiments, qualitative experimental techniques, interviews, questionnaires, etc. The state of knowledge in our everyday practices is concrete, and it refers to particular solutions. If the baby is crying, we’re going to go through specific actions A, B, C, and D and they’re applicable to particular situations. In the scientific research area, our state of knowledge is usually abstract and generalizable. So what that means is that, scientifically, we could say, well, babies, as a group, usually cry for those reasons, and that they respond in particular ways to this particular stressor so we try to look at a group of people and the larger the group, the more valuable our implications are.

And finally, we will go through the interconnections between these two areas of research activities. So everyday knowledge without a doubt can be used as a starting point and a very good foundation for theory development and empirical research. So for instance, if you notice that it is hard for you to acquire a second language, your personal experience and your intuition about what is not working may serve as the basis for your academic inquiry into this topic.

On the other hand, everyday knowledge is increasingly influenced by scientific theories and results of research, especially nowadays because we have access to a lot of cutting edge technology. And we’re always informed about what’s happening in a variety of different research fields. So in that way, our intuition is moving away from being completely implicit. And it starts to incorporate those explicit theories and explicit awareness of different research methods.

Now let us move to the second part of the podcast in which we’re going to talk about conceptualizing your research project. So the steps I’m going to take you through now are going to be, how to choose a research topic, where to start, then how to refine a topic into a specific research question. We will spend some time as well talking about the differences between the research question and the research aim. Then we will discuss the basics of doing literature review, and specifically we will talk about how literature review contributes to us rethinking, reformulating, and continuing to refine your research question. We will also talk about when it is appropriate to do literature review, after selecting a research question, but before selecting a research question, and then we will conclude podcast by talking about how to propose hypotheses

So let’s remember the steps that are involved in research process. we begin with a research concept, which basically means that we need to choose an area of study, something that is of interest to us specifically. Then within that area, we select and formulate a research question. And we conduct literature review to investigate what has been done previously on our selected topic.

The second step is to plan and design a research project. Here we choose and devise appropriate methodology. So, for instance, we select the participants for our future study, and we choose the tools that we’re going to use to test them. At this stage, we’re also worried about applying for and obtaining ethical clearance to conduct our research.

Step three is to step up data management. And here we collect or gather, organize and manage, visualize and analyze our collected results or data. We then proceed to critically reflect on the data that we have collected. And here our task is to interpret the data in light of previous literature to make sense of what results tell us about our research question.

Next, we identify the contributions of the study that we have just undertaken, its limitations, and also outline future directions for future researchers to take. And then finally, we’re talking about dissemination of our research findings. So here, the step involves communicating our research outcomes to a wider community. It may be done orally. For example, research conference or in writing, by drafting up and publishing a research paper on our topic.

So now that we are well acquainted with the steps, now we’re going to specifically cover conceptualizing a research project. Choosing a research topic may seem like a daunting task, especially if there are a lot of areas you’re interested in.

In this section, we are going to look at some common motivations for selecting a research topic.

So first of all, an interest in an area of academic inquiry may stem from simply personal interest or personal experience. For example, let’s think of a second language speaker of English like myself whose first language is Spanish. Many speakers of English that come from a Spanish speaking background wonder how important it may be to attain native likeness to successfully integrate in English speaking communities in Australia. For example, the workplace, the academic environment in which we find ourselves, right?

Additionally, observations of day to day problems or phenomena may also serve as great motivations for wanting to investigate something in more depth. Sometimes when we talk to our friends and family in our home countries, we may want to tell them about a funny conversation or a joke perhaps that we have been told in English that week. But because our friends/parents have got a different L1, Spanish in my case, or Mandarin, Korean, Vietnamese, etc. they obviously interpret the conversation or joke in Spanish, and, the conversation/jokes may not come across as always being funny.

So, we may get interested in the way/techniques that can be employed to effectively interpret and translate humor, in natural conversation, or maybe in literature. A more abstract desire to advance existing knowledge is also a great foundation for selecting a research topic. So for instance, we have all heard that bilinguals are claimed to have certain cognitive advantages over monolinguals but we don’t know much about that topic, thus, we would like to advance existing knowledge in this area. So, a research goal can be to investigate these differences a bit further.

Finally, testing or developing a theory further is also a good basis for research project. Concurrency hypothesis, which is an influential hypothesis in second language acquisition suggests that second language structures that do not exist in the learners’ native language will be difficult to acquire. So, based on this, we can decide to test this theory by looking at the difficulties that learners of Spanish as a second language may have in developing proficiency in the use of subjunctive mood in Spanish.

Another possibility is to look at the paradigm of native-likeness in more detail by exploring whether attaining a native- like accent in English is important (and if so, how important) to integrate in English-speaking communities.

Choosing a research topic is obviously an important step to conceptualizing research project; however, a lot more work still needs to be done to reformulate it as a research question to make the project suitable and manageable. So in this section we will talk about how our initial topics are usually refined into research questions.

So, let’s take one of the topics introduced earlier, wondering how important it may be for a second language speaker of English to attain native likeness to successfully integrate in English speaking communities. So I encourage you to take a

moment here and think about how we can make the statement a bit more specific and a bit more manageable to turn it into a ‘doable’ research project.

So, one thing that we can focus on is the person’s linguistic and cultural background and whether this is relevant? Or perhaps, we can focus on what exactly we mean by native likeness in this instance? are we referring to our accent, maybe to be native like means to use colloquialisms and slang in appropriate situations.

Maybe to strive for native likeness means to attain error free grammar, or minimal disfluencies in one speech, so minimal hesitations, pauses, false starts, self-corrections and things like that.

Another area we can specify is how can we measure integration exactly? Are we going to compare the amount of time a particular person spends with English speaking communities versus the native language speaking communities? Are we going to count the number of meaningful relationships they have with English speakers?

So, you see, answering these questions definitely means that further thought and further refinement is needed. And then finally, what English speaking communities are of interest here exactly? Are we looking at professional or personal context? So here, I encourage you to pause the recording and go to slide 13 and think of the other examples and see what parts of the initial topics suggested there could be refined and narrowed down.

Moving on, here are the steps that are involved in narrowing down your initial topic. Specifically, we need to critically evaluate its every aspect and answer the following questions. What exactly will be investigated? Ideally, here we would like to focus on the single phenomenon. In the research literature this phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a dependent or input variable. So that’s something that we are studying. We can also ask what exactly, who exactly we will investigate.

So here, are we focusing on a single group of people? Or maybe we would like to make a comparison of several groups? Where and in which circumstances will the study be conducted? Or when the issue is investigated, what context are we interested in? What contributing factors are you taking into account?

And here researchers talk about independent variables. So, some things that we are not studying directly, but that can influence the outcome of our research. How will them be investigated? So, here we specify our methodology and we work out the research design. Now, why is it important to investigate, identify and clearly communicate the significance of the current study, either theoretically, or outline its potential practical benefit?

To answer these questions competently, we need to be familiar with the literature; this means, the research that has been previously undertaken in our area of interest. Without being familiar with literature. answering those questions will take a bit of guesswork, which is just not precise enough for a research project.

So, let’s zero in a bit further on what is to be understood as a research question. So, a research question, as mentioned previously, needs to be specific and answerable. That means that, well, the project will usually be conducted within a certain time limit and within a certain budget limit as well.

And you simply would not be able to answer all of the questions you’re interested in. That’s why we try to keep it very particular and very narrow in comparison to our original research area of interest which may be very broad. Research questions usually need to specify variables So the dependent variable is what will be investigated and the independent variables are the factors that may exercise influence or bring change to the dependent variable.

We also need to talk about participants and method, and the theoretical and empirical basis for our research question. So, for example, what models is our research question drawing upon? Finally, we need to be very explicit and clear about why it is important to investigate the issue at hand.

Now, in writing, a research question is often presented as a research aim. So what this means is that we state what we’re going to investigate, i.e, the goal of our project, clearly and unambiguously. Doing this is quite formulaic. So, once you get the gist of it, it will be easy for you to find research questions or research aims in academic literature.

It will also be easy for you to formulate your aims yourselves. So to identify/formulate research questions we look for phrases like, this study aims to explore, the study aims to describe, or the study seeks to examine or investigate, the goal of the study is to address or to verify a given topic, i.e., ‘X’.

So, from the conceptualization of a research project we move to a research topic and then to a research question and then to research aim. Let’s contrast those three concepts.

So the research topic reflects our initial interest in something. And usually, it’s fairly general and fairly broad. The research question is our refined thought about the topic of interest, and its critical evaluation. So when conducting secondary research, the literature review will help us make research question considerably more specific than our original research topic.

And then finally, the research aim is pretty much the same as a research question, but it is reformulated as a statement. And here what we need to remember is that it is of course also specific and that it follows an established and specific structure in writing.

So, let’s work through an example to conclude this section. So, our initial research topic was whether as an English second language speaker, it is important attain native likeness to successfully integrate in English speaking communities.

A research question that’s based on that may look something like this, “what attitudes do international university students in Australia have toward their accents in relation to establishing relationships with their English speaking peers in the group work setting? So, we easily notice how we have specified that the exact group of second language English speakers were interested in is international university students, we have specified the context both broadly in Australia, and specifically, group work setting.

We’ve also specified what we mean by native likeness. So here we’re talking about for an accent in English, and we specified the integration into English speaking communities. So now we are looking at students in a university context and in the process of forming relationships with those peers. Now, that we have this more specific research question, we can go ahead and reformulate it as a research aim, and it would look something like this.

The study aims to investigate the attitudes of international university students in Australia towards their accents in relation to forming relationships with their English-speaking peers. So here you would notice that our research aim is exactly the same as our research question, but just presented as a statement.

Let’s move forward in the session and let’s focus on the role of literature in research. The literature refers to the relevant previous studies that have been conducted in our area of interest. And a literature review then means searching, reading and reviewing that literature.

Literature Review, as a term refers both to the process of reading everything that has been written on the topic and the product, ie., a written summary and analysis on what we’ve read. And here it is important to remember that literature review has to be both a little bit descriptive, so it tells us about what has been done, but also very analytical because it evaluates the contribution of previous studies.

So, the literature review is a good way to find a starting point in your project because to determine the next step, we need to know where we are currently at. So, the literature review tells us is what has and has not yet been done on the subject. It also helps to identify a gap in the current knowledge on something. So, it serves as a justification for new

research projects to be undertaken.

If something is well-known, the Literature Review can still provide us with new ideas. Many articles conclude by discussing the limitations and explicitly provide recommendations for further research and future directions. So if you feel like you’re a bit stuck with formulating your research question, it’s always good to read the discussion and conclusion sections of research papers because they provide you with a lot of suggestions.

And finally, the literature review can serve as a good model because seeing how others approach a similar issue may provide ideas for your own project. So questions like, who did they test and what methods did they use can inform our own methodology.

The literature review serves multiple purposes as you will have already seen. So, first of all, it provides us with a historical background on a specific topic. And usually here we refer to some cool seminal work. It also provides contemporary context with recent publications. So what are other hot topics now in your area? The literature review introduces us to theories and concepts in our area of interest. And it also helps us to specify and define relevant terminology.

So it’s very important for the purpose of the literature review as an end product to really guide your reader into the area that we have academic interest in a way that is always unambiguous and clear and providing terminology. And this unambiguous stating of new terms is a very important component of that.

The literature Review also identifies gaps, limitations and shortcomings of previous research. So, it is a sign of a good research paper when it is being upfront about some of these shortcomings and encourages future research to fill in the gap.

The literature Review identifies the significance of the issue being researched. Sometimes the significance can be found in something that has been very thoroughly investigated, because if it’s still sparks interest, it means that the area is of critical importance. On the other hand, the significance may be in the fact that something has been understated and therefore new knowledge is required to really understand that area.

There are certain misconceptions that a lot of people hold about the literature review. So, on slide 23, we’ll attempt to debunk them. So, first of all identifying a research topic and a research question and conducting literature review do not have to happen sequentially, one after the other, rather, they happen cyclically.

So, what this means is that you may start with a research topic, and with the help of the literature review you narrow it down to a research question. Or you may start with a particular question, but then in the process of the literature review, you may change it, you may broaden it, or you may switch to a new question altogether.

Or the third scenario is that you don’t necessarily have a topic or question in mind and you’re sort of just reading broadly to familiarize yourself with what has been done previously. And in the process of the literature review you arrive at a topic, and then at a question.

Now, the literature review should not be viewed as a collection of references and citations. On the contrary, you need to be actively involved in interpreting the literature that you’re reviewing, and also in explaining that interpretation to the reader. So, remember how we said that we should be guiding the reader through the literature review? Well, this’s what that’s about.

You shouldn’t just be listing what others have written. At the end of the day, the literature review process is not about presenting the points of others, but about relating those points to our own idea and argument and about using them to set up and justify our research question. So previous literature is a tool that you use to really motivate your own study.

Now to effectively conduct a literature review, we need to be familiar with some of the common types of research papers. So, first of all, we can encounter theoretical papers and they draw upon currently published research literature with the aim of furthering theoretical work in a field of interest. In most of cases, theoretical papers would summarize and critically evaluate current research.

Argumentative/position or response papers are usually structured as opinion pieces that often present an arguable opinion about a topic and recommend a particular course of action. Such papers could evaluate theories in relation to a real-world phenomenon, and then suggest that one theory is a more accurate account of what is actually happening.

Empirical papers are based on observed and measured phenomena, so they actually collect data and they derive knowledge from actual the reading of coded experience of collected information, rather than just a theory or belief. Empirical papers are often based on theories and models, but the source of their conclusions comes from the original data. Pilot studies is a crucial components of the main study will be feasible or achievable, allowing the researcher to adjust course correct and fine tune the study before actual implementation. So, it can be the case that somebody runs a pilot study before conducting an empirical study and writing an empirical paper.

Editorial papers are brief articles written by an editor of a journal, and they may provide an overall description of a newly released issue or express editor’s opinion about the topic of focus issue. Those papers are combination of a theoretical paper because they draw upon currently published research and an argumentative response paper, because the usual represent an opinion of an editor.

Let’s conclude this section with some reflections on how we conduct a literature review. This is the topic that we will be covering in depth in this week’s tutorial. But before we meet, in preparation, I’d like for you to ask yourself the following questions: where and how do you find relevant literature? To answer this question you can draw on your previous experiences in maybe conducting research projects for one of your other subjects.

Also, how do you determine which papers should be given priority? So, in other words, which ones would you read first, and why? What clues are you looking for when you’re making this decision? Now, how to read the selected papers efficiently is a question that takes us to the issue of how to quickly realize that a certain paper is useful or not useful for our study. Additionally, how to move on, how to manage and keep track of your reading. So, do you have a system in place that helps you organize your thoughts about the papers that you have read? Food for thought…

And finally, how to organize and structure our writing? This is an important question, because writing the literature review is one of the most challenging components of writing a research proposal or a research paper based on a research project because it really needs to highlight the crucial aspects of our current understanding of a certain issue. So, take your time, think about those questions, and then we’ll discuss them when we meet next week.

We’re going to conclude our today’s discussion by talking about formulating proposing hypothesis. I guess the question you may want to ask here is how is our research hypothesis different from research questions. Well, hypothesis are potential answers to research question. Sometimes they’re also referred to as predictions in the research literature.

Hypotheses are based on what is known about the topic under investigation. So basically, to formulate a hypothesis, you need to be familiar with previous research, if only little is known about a certain topic, so if not a lot of research is available, it is of course difficult to formulate hypotheses.

That’s why you’ll see that some studies do not have hypotheses, they just conclude the literature review by formulating a specific research question. It is a good practice and an expected practice to formulate hypothesis before data collection and then the collected data either supports or rejects the original hypothesis; it is also possible to formulate a competing hypothesis.

So, for instance, if you’re reviewing multiple theories in literature review, you can say that according to theory A, it is expected that one thing would happen. But conversely, following the research of B, it is predicted that another thing would happen. And so, formulating competing hypothesis is actually quite common.

Now let’s have a look at an example. So we’re returning to our proposed study, which aims to investigate the attitudes of international university students in Australia towards their accents in relation to forming relationships with the English speaking peers in the academic group work setting. Here it is possible to formulate a number of different hypotheses.

So the first type of hypothesis assumes that there is no relationship between the factors and doing nothing in technical terms, such hypotheses are called no hypotheses. So here we can say that international university students in Australia believe that their accents are unrelated to forming relationships with our English speaking peers in a group work setting.

So it implies that maybe other factors are more important than somebody’s foreign accent. We can also predict non directional relationship, which is a broad hypothesis. So here we would say something like, international university students in Australia believe that their accents affect relationships with their English-speaking peers in group work setting. So here you will notice that there is a relationship established between accents and forming relationships with English speaking peers, but we don’t know the direction of this relationship, does it affect the relationships positively or negatively?

This type of hypotheses never specifies that. And then finally, we can formulate a directional hypothesis or we can assume a directional relationship. And this is the most specific type of the hypothesis. So here we could say that international university students in Australia believe that their accents positively affect relationships with their English speaking peers in a group work setting. So here, well, not only are we establishing a relationship, we’re also giving that relationship a direction, we suggest that the relationship will be positive.

We can of course, formulate a competing hypothesis which is also going to be directional and say that accent negatively affect relationships with English speaking peers, and then we can test those competing hypotheses. As you will have guessed by now, the last type of hypothesis is preferred because it gives us the most specific lock on what is going to happen.

Alright, so let’s summarize what we have learned today. As human beings we naturally and frequently engage in research activities in our daily lives. And usually that happens in response to some problematic event because our desire is to solve it as quickly as possible.

Academic research can be viewed as a research activity that is quite comparable to everyday research, but it is a more formalized and structured process. Research in general aims to increase our knowledge on a particular topic. And as we have discussed when we’re formulating a research topic or a research question, we need to aim to make it as narrow and answerable as possible.

Different types of research approach this aim quite differently. So basic research advances our knowledge regardless of its application, so it’s gaining knowledge for the sake of gaining knowledge. Applied Research, on the other hand, aims to solve real life problems and assess real life issues.

In the second part of the podcast, we talked about conceptualizing a research project which consists of three very important steps, choosing an area of study, formulating a research question or research aim, and a research hypothesis, if possible, and conducting your literature review.

What is crucial to understand and remember, though, is that these three steps are not linear, but cyclical. So, you can start with either of the three and move freely between them. Generally speaking, however, we’re moving from a broad understanding of a particular topic to a more specific issue.

Finally, it is crucial to know that literature review is an essential foundation for any new project. So Basically, to design your own study, you first need to be very familiar with what has been done previously. So I hope you enjoyed this first lecture. And we’re wishing you a fun semester ahead. Thank you.

The Scientific Circle

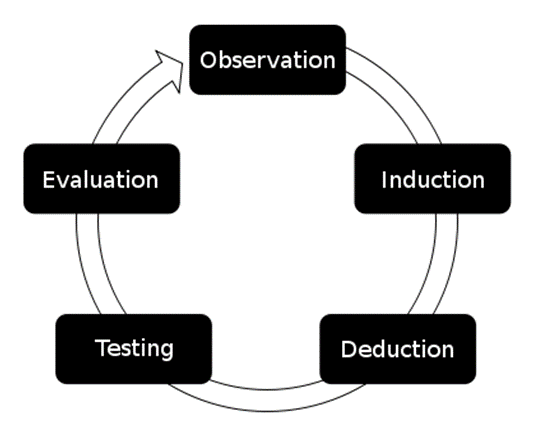

Empirical research typically follows the scheme described below. This scheme is also referred to as the scientific circle and we will use the example of having lost your keys to exemplify how it works.

So, let’s imagine you lost your key: in a first step we make an observation (keys are not here). In a second step, we ask ourselves where the keys may be (research question). In a third step, we come up with an idea where the keys may be (hypothesis). Then, we think about where we have lost the keys before (literature review). Next, we look for the keys where we expect them to be (empirical testing), then, we evaluate the result of the test (was hypothesis correct), and finally, we either have found the keys (hypothesis was correct) or not (keys are still missing) which causes us to come up with another idea and we need to go through the same steps again.

A slightly more elaborate depiction of this scenario with the equivalent steps in the scientific circle is listed below.

- Make an observation (e.g., My keys are gone!)

- Formulate a research question (e.g., Where are my keys?)

- Deduce a test hypothesis (H1) based on observation (e.g. My keys are on the table next to the TV!)

- Formulate null hypothesis (H0) (e.g., My keys are not on the table next to the TV!)

- Determining the level of significance at which the H0 is rejected

- Formulate potential results: what results are possible and what do they mean for the H0 and H1? (My keys are not on the table next to the TV!: H0 cannot be rejected, formulate new H1)

- Design experiment/study/research (e.g., I will go over to the TV and see if my keys on the table next to the TV.)

- Conduct experiment/study/research (e.g., Actually go over to the TV and see if my keys on the table next to the TV.)

- Statistical analysis

- Interpretation of the results (e.g., My keys are not on the table next to the TV so I must have lost them elsewhere!)

- In case H0 could not be rejected: Formulate new H1. (e.g., My keys are on the kitchen table!)

Think Break!

`

Apply the scientific circle to a study of the existence of the Loch Ness monster.

You want to investigate whether the speech of young or old people is more fluent: how could you go about testing this?

`

We will stop here with our introduction to quantitative reasoning. If you are interested in learning more, we highly recommend that you continue with our tutorial on basic concepts in quantitative research.

Activities

Activity 1: Who are you?

This activity aims to give you an idea about your fellow students and to get acquainted with them.

You will be sent into break-out rooms in small groups. Introduce yourself to the other members in the break out room:

1. What is your name?

2. Where are you from?

3. Where are you right now?

4. What is your age?

5. Have you studied at another university before?

6. Do you have hobbies?

7. Tell them something unexpected or interesting about yourself.

8. What do you think this course will teach you?

Activity 2: What is research?

This activity aims at making you reflect on research and the characteristics of scientific inquiry.

You will be sent into break out rooms in small groups, please discuss the following questions and post your answers on the Padlet for this week.

- How would you define research?

- What are necessary components of research?

- How can we distinguish research from unscientific activities?

- Discuss why research needs to be methodological.

Activity 3: Is this research? (Scenarios taken from Borg, 2009)

The purpose of this activity to elicit your view on the kinds of activities that can be called research. There are no right or wrong answers. Read each description below and choose one answer to say to what extent you feel the activity described is an example of research by selecting one of the following answer options, and then give reasons.

Answer options: Definitely research Probably research Probably not research Definitely not research

When you finish the task yourself, compare and discuss your answers with your neighbor / in the break-out room.

Scenario Research? Why?

1. A university lecturer gave a questionnaire about the use of computers for language teaching to 500 teachers. Statistics were used to analyse the questionnaire results. The lecturer wrote an article about the work in an

academic journal.

2. To find out which of the two methods for teaching vocabulary was more effective, a teacher first tested two classes. Then for four weeks she taught vocabulary to each class using a different method. After that she tested both groups again and compared the results to the first test. She decided to use the method which worked best in her own teaching.

3. The Head of the English Department wanted to know what teachers thought of the new course book. She gave all teachers a questionnaire to complete, studied their responses, then presented the results at a staff meeting.

4. A teacher was doing an MA course. She read several books and articles about grammar teaching then wrote an essay of 6000 words in which she discussed the main

points in those readings.

5. Two teachers were both interested in improving discipline in their classes. They observed each other’s lessons once a week for three months and made notes about how they controlled their classes. They discussed their notes and wrote a short article about what they learned for the newsletter of the national language

teachers’ association.

Activity 4: Types of research

What types of research correspond to what number?

Activity 5: Conducting research

Put the following possible steps of conducting a research project in an order that you think is appropriate.